Blood Tests: Reliable Suicide Detectors?

JANET GUAN

Staff Writer

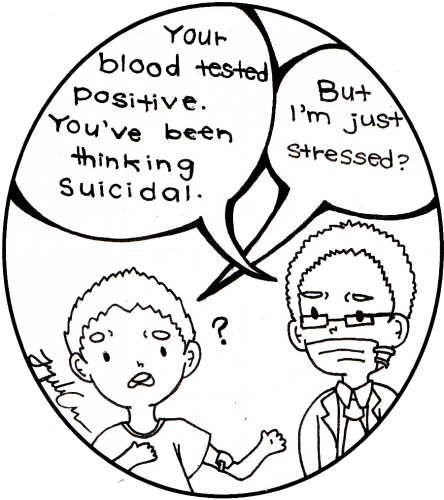

Depression has become an impacting illness in the United States. According to Centers for Disease Control, in 2008, one in ten adults reported to having depression. Depression decreases a person’s ability to do normal activities, but it greatly affects the person’s mental health as well; it can lead to the decision to take one’s own life. Many people almost never disclose the morbid thoughts they have, making imminent suicide difficult to detect. However, scientists are looking into a blood test that can possibly identify when a person is at risk of suicide.

The blood test’s purpose is to find select biomarkers, molecules indicating how active certain genes are. The high or low expression of specific genes can determine whether the people are thinking about suicide. The research team, led by scientists from the Indiana University School of Medicine and the VA Medical Center in Indianapolis, performed their study on a group of white men with bipolar disorder. They met with the researchers every three to six months, giving blood samples and answering psychiatric tests at each visit.

Nine of the patients had changes in their suicidal thinking due to emotional disorders, and the blood samples drawn from when they had suicidal thoughts had high expressions of the gene called SAT1 and the low expression of the gene called CD24.

The researchers also examined blood samples from nine men who had killed themselves, as well as another group of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Both also had high expressions of the gene SAT1. Though these tests have had consistent results, it is far from becoming a reliable test because of multiple factors that may counter its accuracy.

First, the study was done predominantly on a group of white men. In order to be considered a reliable test, the test should be applicable to all who are susceptible to depression. This includes women, who are more likely to be diagnosed with depression, as well as those living in unfavorable situations, such as those who have recently experienced a divorce or separation. Patients of different races and ages should be considered to see whether the test is applicable and consistent to all people.

Second, the appearance of the biomarkers did not indicate the degree of the suicidal thinking. Scientists cannot measure the intensity of depression a patient is feeling. Questionnaires may allow scientists to have a general idea of how the patient is feeling, but the intensity of suicidal thinking is only known by the patient.

It is difficult to exactly measure the intensity of depression when the scale the patient is basing their depression on may differ from how researchers interpret their feelings. The test leaves the question of whether the genes are also expressed when the patient is experiencing depressing, but not suicidal, thoughts.

Third, most people do not take blood tests often. Unless they have certain medical conditions, the frequency of blood tests depends on how often the doctor requires the patient to be tested. Patients with depression may be able to start having routine blood tests, but it does not take into consideration the people who do have depression, but are undiagnosed. A person on average has three doctor visits per year, and the high cost of health insurance and consequently doctor visits may discourage people from visiting doctors.

Using biomarkers to indicate whether a person is about to commit suicide can possibly prevent multiple deaths, but more research is needed to define the specific nature of the genes. Instead of focusing on detecting suicide thoughts, detecting depression and finding more effective ways to treat depression can counter both depression and suicide rates.